Don't Forget to Breathe by Thomas Wolf

Here are three questions about teaching and learning.

1. Which is better? A teacher who praises and instructs through encouragement or one who criticizes and is only looking for things to fix?

2. Which is better? A teacher who guides you primarily by demonstrating how to do things or one who is always observing and commenting on what you are doing?

3. And finally, which is better? A single great teacher whom you admire above all others or at least two teachers who have different approaches to the same subject matter?

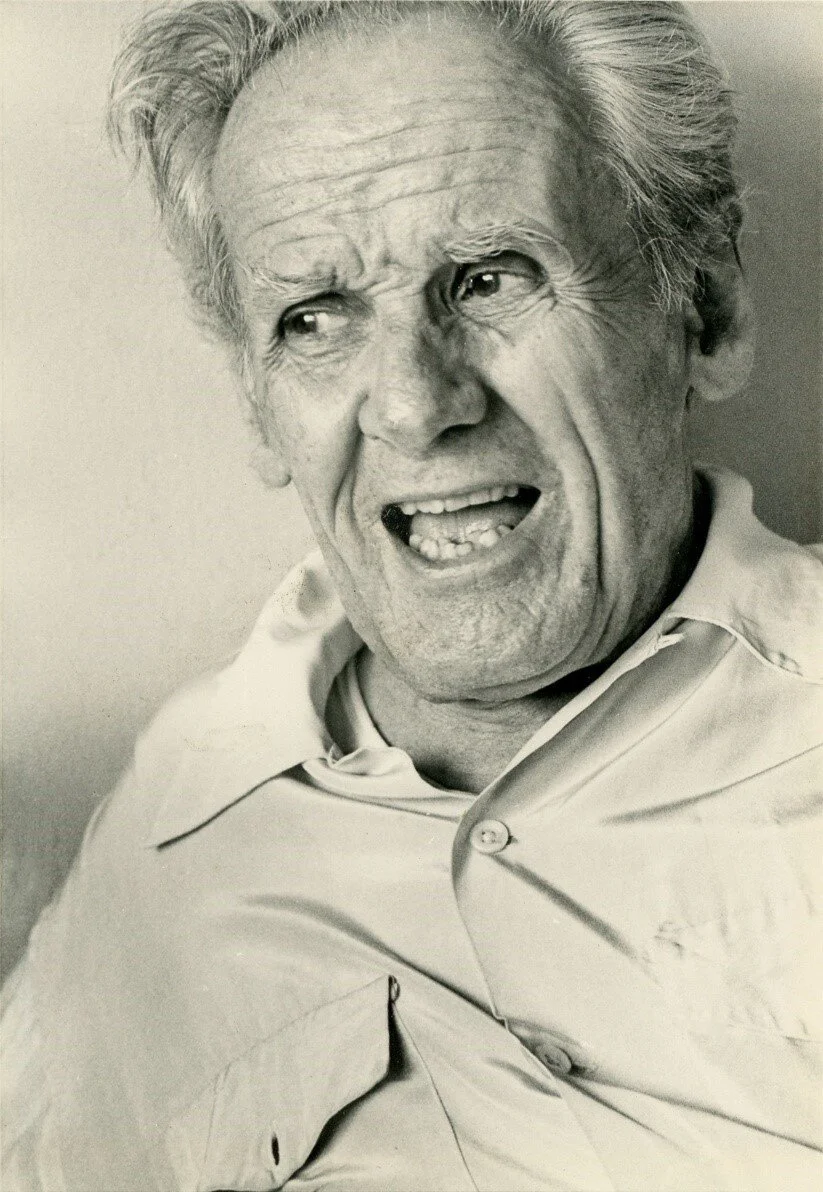

Flutist William Kincaid, working out at his summer home in Grey, Maine, in 1960. To me, Kincaid was the greatest of flutists [Billy Wolf photo].

My experience learning to play the flute gave me first-hand insight into these questions. I was lucky enough to study with two of the greatest flutists of the twentieth century. The first was William Kincaid, the principal flutist of the Philadelphia Orchestra, whose playing I most admired. In addition to studying with him in Philadelphia, I would travel to his summer cottage in Grey, Maine where he regularly kept in shape working out with a punching bag.

Kincaid was easy-going, mostly encouraging, and taught by example, often playing a great deal in my lessons to illustrate what he wanted.

Flutist Marcel Moyse at a masterclass. He was often not happy with what he was hearing and his face always gave him away.

My other teacher was Marcel Moyse, who had played principal flute in numerous French orchestras and was one of the leading flute soloists of his generation. Moyse was a tyrant who spent most of the time criticizing and twice led me to consider giving up the flute entirely. He played almost not at all in lessons or masterclasses and, when he did, it was generally to illustrate a few notes or a phrase, rarely an extended passage.

So let’s start with the first question: which approach is best—encouragement or criticism?

I am firmly convinced that the best teaching style depends entirely on the student. Let us assume the student has had good basic training and is ready for advanced work. For those who are self-motivated—like my brother Andy, who actually enjoyed practicing four or five hours a day and whose self-confidence was sometimes an issue—the more encouraging approach was best and he progressed most rapidly with the teachers who employed it. For me, who didn’t especially like to practice and was perhaps a little too full of self-confidence, the shock treatment of a teacher like Moyse was precisely the approach that best suited my needs. It wasn’t fun—indeed it was often misery and reminded me all too often of the early years of violin study with my grandmother. But, truth be told, it was under Moyse’s guidance that I made the most progress as a player.

As to the second question, a teacher who guides you primarily while demonstrating what he wants you to do may not be addressing the specifics of your own playing and providing the guidance you require. On the other hand, some students do best by listening to great playing. While I was mesmerized and loved listening to Kincaid play in my lessons, it was not nearly as much help as having Moyse listen attentively to everything I did and comment at a micro level. Andy, on the other hand, was influenced by the playing of his teachers, especially one of them, Mieczysław Horszowski. It was the way this teacher actually approached the instrument that inspired my brother’s learning the most.

On the third question—is it best to study with one great teacher who you admire or more than one?

Andy and I would have answered the same way. Never limit your study to one great teacher as you may end up a poor imitation. If possible, study with at least two teachers who have very different philosophies and you will end up forging your own style. This proved to be the case with both Andy and me. His initial years with Eleanor Sokoloff, a teacher best known for her work with talented young students, had given him a solid technique. Then he studied both with Rudolf Serkin and with Mieczysław Horszowski, just as I had studied with Kincaid and Moyse. Both of us benefitted from this multifaceted approach.

This was also the situation with our Uncle Boris Goldovsky (who enjoyed a wonderful career as a pianist, conductor and opera impresario, and he talked quite frankly about his experience. His studies with Artur Schnabel led him for a time to become a caricature of the great man’s playing, a situation he described in his autobiography as a “crippling,” overpowering influence “that had robbed me of my artistic individuality.”[i] As he explained to my brother and me, “I ended up being a banger after studying with Schnabel, and it was only after I studied with Ernst von Dohnanyi, whose approach could not have been more different than Schnabel’s, that I was able to incorporate both approaches into a style that was more appropriate to my personality and ability.”

One of the more interesting examples of multiple influences on a musician’s development is the case of the violinist, Yehudi Menuhin. After studying briefly as a beginner with Sigmund Anker, he moved on to Louis Persinger at age six and was with Persinger during what were considered his “child prodigy” years. The plan was then for Menuhin to move on from Persinger to Eugène Ysaÿe who had been Persinger’s teacher (and incidentally was the teacher of my grandmother, Lea Luboshutz). But given Ysaÿe’s age and poor health, the plan changed and Menuhin went to study with George Enesco, who like Ysaÿe was of the Franco-Belgian school of violin playing. After this phase of his musical development, something rather unusual happened. Enesco decided to pass Menuhin on to Adolph Busch, someone whose playing he did not particularly care for but someone who was an important musical force at the time.

As Yehudi Menuhin’s father recalled in a book about the family: “Enesco respected the serious, precise, scholarly approach of the German musicians but he did not like the German school of violin playing. He thought that the Germans were too heavy, too even, too dry, that they could not make the violin sing as delicately and elegantly as the Franco-Belgian school. He told Yehudi: 'My dear Yehudi, you belong to the Franco-Belgian school. Nevertheless, one day you must have a good and solid contact with the German school of violin-playing. Some day you must study with Adolf Busch, the best exponent of the German school of violin-playing.After some time with him, you can come back to me, if you wish.'”[ii] And so Menuhin was exposed to a completely different approach which enriched his understanding of the instrument.

SYRINX, an oil painting by Arthur Hacker (1892) in the Manchester Art Gallery in England

This sets the stage for a story of a piece of music that I studied with both of my teachers, Kincaid and Moyse—a short solo for flute called Syrinx by Claude Debussy, composed in 1913. The piece is based on the Greek myth about the beautiful but chaste nymph, Syrinx, who is pursued by Pan, the oversexed Greek god of the wild, of nature, of hunting, and of music. Syrinx has been portrayed often by artists but my favorite oil painting is Arthur Hacker’s from 1892 that I had the pleasure of viewing in the Manchester Art Gallery in England.

According to the story, Pan’s attentions made Syrinx fearful and unhappy and she sought assistance from the river nymphs who turned her into a hollow reed growing on the bank. Pan chased Syrinx to the river and, believing that the reeds were hiding her, he cut them down. Unhappily, he did not find her, but when he sighed over the reeds, he discovered that they give forth musical sounds. He fashioned reeds of different lengths into a series of pipes, bound them together, and, lo and behold, he created an instrument of rare beauty—panpipes—the precursor of the modern flute.

Photo of panpipes. Though the instrument has been widespread throughout the world for centuries, this particular instrument comes from the Solomon Islands.

Syrinx is a perfect piece for an encore—only four minutes long and with a wonderful backstory for an audience to enjoy. I had studied it with Kincaid and had performed it many times before bringing it to Moyse. Kincaid was most interested in the quality of the sound, which he demonstrated beautifully. He told me of his experience in the Philadelphia Orchestra when the group, led by conductor Leopold Stokowski, was recording another piece by Debussy featuring the flute—the hauntingly lovely Afternoon of a Faun. To get the distant mystical sound that Stokowski wanted, Kincaid put a handkerchief over his fingers to diffuse the sound coming out of the finger holes. Though he did not suggest I do this with Syrinx, he demonstrated precisely the sound he wanted. Interestingly, he didn’t particularly care where I took my breaths so long as the phrasing seemed musical. There were breath markings in the music but I knew that in general, such indications are not entered by the composer, and are rather suggestions by subsequent editors. I always took pride in the fact that I could come up with better ideas than a mere editor.

The day I played Syrinx for Moyse for the first time, I felt confident. I had performed it so often before enthusiastic audiences that those hundreds of people couldn’t be wrong. Besides, he seemed in a jovial mood—always a good sign. He smoked his pipe and told me to play. I did so and he sat quietly. When I finished, he asked me to play it again without making any comments—a bad sign. I played it a second time and he asked me innocently:

“Ah, you do not like za breezing [the breathing] in za musique?”

“Oh,” I said confidently, since Moyse himself often criticized the markings of editors. “I don’t think the markings are as musical as the places I chose to breathe.”

Silence.

Then. “You don’t like what is written in za musique?”

“Well,” I said hesitantly, knowing now I was headed for a trap. “As you often say, you cannot always trust an editor to come up with the best phrasing.”

“Perhaps I tell you a story,” said Moyse. And he did: of a night when he and Debussy were attending an evening party at which a short play was to be presented including the tale of Syrinx. And of how the hostess had said to Debussy that since Moyse was there with his flute, perhaps Debussy might sketch out a little music for Moyse to play. And how Debussy quickly sketched out Syrinx and then indicated to Moyse how he would like it to sound. Then came the clincher. Debussy and Moyse jointly agreed on where would be the best places to breathe and Moyse promptly indicated these in the manuscript.

Then Moyse looked at me and said, “But meh-bee you know better zen Debussy.”

I will never forget those words. And from that day to this, I have always taken a breath where the music indicates.

[i] Boris Goldovsky and Curtis Cate, My Road to Opera: The recollections of Boris Goldovsky. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1979, pp. 72-73.

[ii] Menuhin, Moshe, The Menuhin Saga, London: Sidgwick & Jackson Ltd, 1984, p. 104.

![Flutist William Kincaid, working out at his summer home in Grey, Maine, in 1960. To me, Kincaid was the greatest of flutists [Billy Wolf photo].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c48b94c2714e5229b8adc61/1597935590208-EN4QG70GQHZ370LCW6I2/William+Kincaid)