You Have to Start Somewhere by Thomas Wolf

How does a parent know when a child is ready to take on a new challenge in life—whether it is riding a bicycle, taking the subway without an adult, or playing a first concert? Sometimes the question is easy to answer. At other times, it appears to be more difficult.

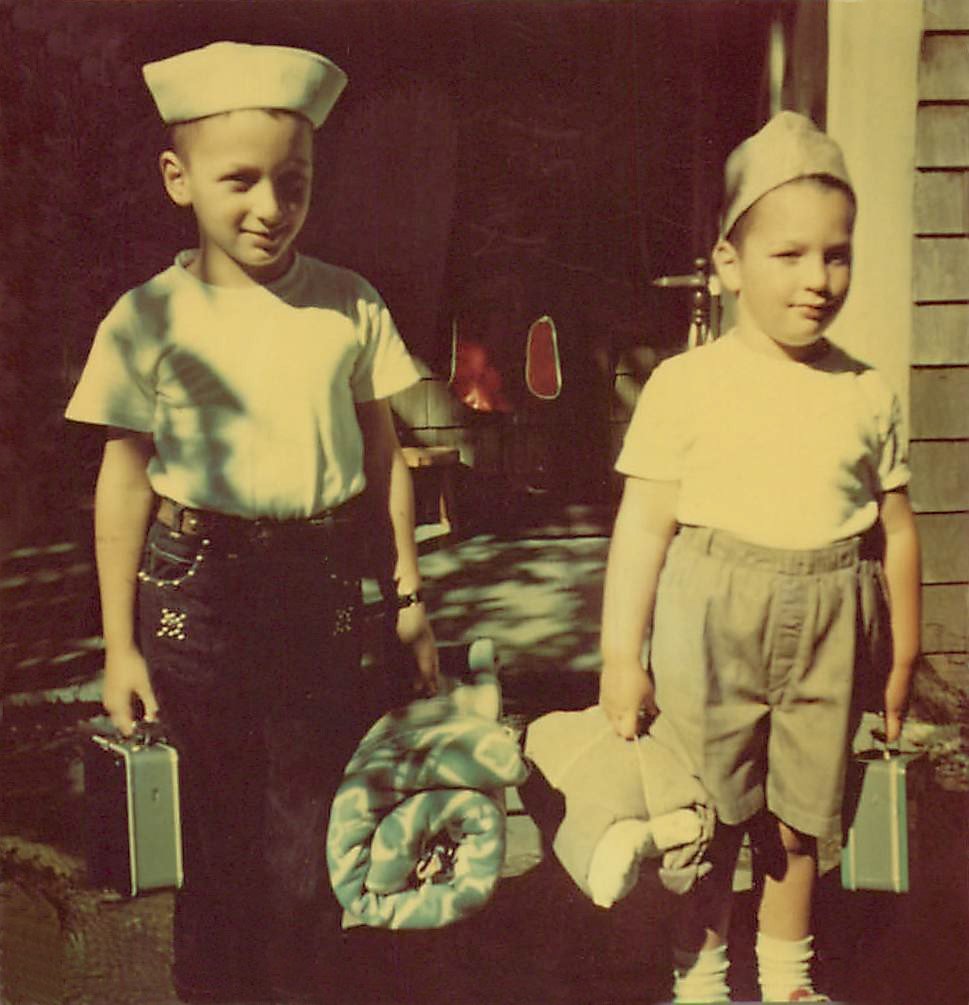

My brother Andy (left) and me leaving the house to go to summer day camp.

We had already had our daily violin lessons with my grandmother who began her day quite early.

Each of us in our family started learning to play an instrument at a young age. Knowing when to start wasn’t a difficult decision as far as the elders were concerned. If you were old enough to stand on your own two feet and understand simple instructions, you were old enough to hold an instrument and begin lessons. By the time my brother and I were ready to go to day camp in the summer, we had been receiving music lessons from my grandmother for several years.

In my Uncle Boris Goldovsky’s case, he started on piano so young that in later life, he couldn’t even remember how old he was when he began. Though his father, Onissim Goldovsky, was an attorney, he was also an accomplished pianist. The older man believed that his son should follow in his footsteps and learn to play an instrument at a professional level no matter what his ultimate occupation. That would always be an asset and a mark of culture. As far as my violinist grandmother was concerned, children would not amount to anything unless they started playing an instrument early in life.

Uncle Yuri in a university photo after his piano studies were over. Though he was destined to become a mathematician, the early piano training allowed him to play well enough to earn money as an accompanist at a dance school run by Isadora Duncan.

Both Boris and his older brother, Yuri, began their piano studies in Moscow under the guidance of their Uncle Pierre Luboshutz, a professional pianist. Since Boris’s musical gifts were superior to those of his brother, it was decided that he should become a professional musician and great effort was poured into ensuring that he would be able to compete at the highest level. Family wealth allowed for excellent training, including related studies in music theory, ballet, and theatre. Interestingly, though brother Yuri would abandon his piano studies and become a university mathematic professor, he still played well enough thanks to his training to earn money by playing piano at Isadora Duncan’s dance school. Starting early had literally paid off.

In Boris’ case, since he was destined for the concert stage, the question of “when” that was to occur became a much more complicated question, indeed a conundrum. In many ways, Boris seemed ready to concertize by the age of ten when he already played better than many adult professionals. Yet the family wasn’t convinced that it was a good idea to push the boy onto the stage, as so many other parents around them were doing—with catastrophic results. Boris’s mother had already had experience overseeing the musical development of her two younger siblings and she did not want to rush Boris. Better for him to master the instrument, build a large repertoire, and, most important, practice.

But in 1917, when the Russian Revolution broke out, the family situation changed drastically. Boris’s timetable had to be advanced. My grandfather’s legal practice (and income) was much reduced. Being a moderate politically, he was reviled both by the right (those loyal to the Tsar) and the left (the Bolsheviks). Neither group was interested in hiring him. The family would have to rely on income generated by my grandmother’s concerts. But this income too was in jeopardy. By the time the Bolsheviks had taken full control, many concert opportunities were relegated to factories, where musicians were hired to play for the workers in exchange for meager amounts of food.

Lea played many factory concerts, often taking her brother Pierre as her accompanist, as this meant additional food for the family. When Pierre could arrange a solo program on his own, however, he always preferred it since he was “paid” more than he received as a mere accompanist. On the occasions when both had concerts on the same day, another pianist by the name of Semeon Samuelson (a Gold Medal winner at the Moscow Conservatory as my grandmother had been) was pressed into service as Lea’s accompanist. Meanwhile, young Boris, age 11, begged to be used when his Uncle Pierre was not available. He knew many of Lea’s pieces already and he could earn for the family as well. Boris’s pleading was at first considered a wonderful joke. While he was obviously talented, his mother felt he still wasn’t ready for the concert stage. Better to use the time to practice.

Then came the event that launched his career.

Both Lea and Pierre had separate concerts on the same date and Samuelson was ill. What to do? Cancelling was out of the question—the family needed the food. In desperation, Lea decided to use Boris. Dressed in his sailor suit, Boris tried to look as old as he could. More important, he practiced and rehearsed with his mother as if his life depended on it.

Young Boris makes his successful debut with Lea in a Soviet factory.

The concert, as it turned out, was a sensation—not because of Lea’s extraordinary playing but because of Boris. The boy made such a great impression on the workers that Lea was immediately re-engaged, “so long as you bring the boy again. That young son of yours was fabulous,” the factory foreman said, “and the workers loved him. Next time, if he plays something by himself, we will pay him as a soloist as well.”

And so began Boris’s solo career. The piece he chose (actually chosen for him by the family elders) for his solo debut was Mendelssohn’s wonderful Rondo Capriccioso, not an easy piece by any means but one that Boris in later life often used as an encore, telling the story of his debut with the piece. Years later, he made a recording of both the Mendelssohn composition and the story. Sadly, much as I have searched, I cannot find it. So here is an alternative—a wonderful recording of the work by pianist Claudio Arrau (with the bonus that you can follow along with the music).

And in case you are looking for a life lesson from this story, perhaps it is that there is nothing quite like the combination of motivation and necessity to ensure readiness for a new challenge.