Technology and Music—New Ways to Listen and Learn by Thomas Wolf

In a past blog post, I wrote about the future of classical music video. It generated a good deal of interest and some readers suggested additional examples of video that might enhance the article. I have continued to update that blog post and the latest version can be found here. I was also pleased to receive a call from a symphony orchestra wanting to pilot some of the ideas. I continue to believe that video and other technology, creatively employed, offer many possibilities for additional enjoyment by classical music audiences.

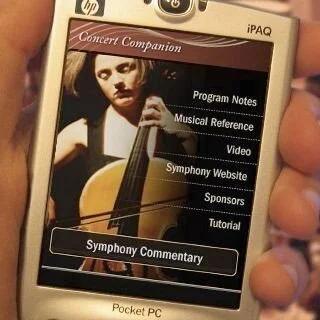

In this post, I continue the theme of how technology can enhance the audience experience. One idea is to offer commentary and conversation to accompany the music in real time (as the music is being played) using technology. The idea is not new. Indeed, the concept of simultaneous musical commentary goes back at least to the early 2000s when Roland Valliere, the then-executive director of the Kansas City Symphony, developed something called the Concert Companion, a hand-held device that offered concert listeners streaming program notes synchronized with the music along with additional commentary.

(Credit: Opera Glass Networks)

The idea was simple. When something interesting was about to happen in the music, the screen would show a text-based description helping audience members become aware of important moments in a piece. Among other things, Valliere wanted to address the age-old problem with printed program notes. If you read them before a performance, it is nigh on impossible to relate what you have read to the musical moments they describe once the music begins. Imagine reading something like, “In the final movement, a contrasting secondary theme is heard in the woodwinds after the initial rondo theme has been repeated twice by the strings.” By the time you have been listening to three previous movements, what is the chance you will remember this sentence, especially if it is one of a dozen or so? And what is the chance that your ears will be sharp enough to pick out the musical theme to which the printed material refers? If you are like me, you may skip those parts of the printed program notes, realizing that they will do you very little good when you are in the throes of the performance itself. Valliere’s idea was to offer the listener the musical description at the very moment or immediately prior to it occurring in performance by reading about it on the hand-held device. The device would also offer conventional program notes for reading prior to the performance with historical and biographical information. Here is an example of some of the pages from notes to Stravinsky’s “Firebird,” beginning with pre-performance background and, with the last slide, initiating the synchronous streaming.

(Credit for all images above: Robert Winter and Peter Bogdanoff)

Valliere’s concept was so exciting that several foundations funded pilot efforts to get the effort started and a number of symphony orchestras agreed to test the device. The New York Philharmonic, the Philadelphia Orchestra, the Pittsburgh Symphony, the Kansas City Symphony, the Oakland East Bay Symphony and the Aspen Musical Festival all decided to try the Concert Companion over a three-year period. Meanwhile, Valliere’s idea captured the interest of people in Silicon Valley. A company was formed in partnership with the Juilliard School and initial seed funding was forthcoming. But the economic downturn in 2008 froze additional seed funding and eventually the effort fizzled.

But developmental funding was not the only problem with the Concert Companion. The business model simply did not work. Piloted before the age of the iPhone and apps, it required the purchase of specialized hardware for each user, making it an expensive proposition out of the gate. It also required a trained individual who would advance the text as the music played—another expense for musical organizations that were often struggling to meet their budgets. Yet another predictable problem was the attitude of musical purists for whom the idea of devices in the concert hall was an anathema. In some cases, special seat sections had to be reserved for those with the Concert Companion device so as not to distract conventional concert goers, but subscribers are generally loath to give up their regular seats.

Valliere described the Concert Companion as similar to audio guides in art museums. “I was trying to do for symphony orchestras what audio guides have done for museums: enhance and enrich the experience in real-time,” he was quoted as saying. But audio guides do not have a time sequencing pressure associated with them like music does and they do not distract from other viewers’ experience. If I don’t like someone listening to an Acoustiguide when they are viewing a painting I want to look at, I simply go look at another painting until that person is done. That is not possible in a musical performance. We all have to experience the music at the same time.

Leon Fleisher

Finally, there was the challenge of what musicians might think about having the concert experience mediated by a hand-held device. Indeed, one musician, pianist Leon Fleisher, threatened to cancel his appearance with the New York Philharmonic if the Concert Companion was employed when he was playing his solo.

Many other musicians performing an important concert with a world-class orchestra would find Fleisher’s position reasonable. (For more on the Concert Companion, two interesting articles can be found here and here.)

I believe there is much to learn from the Concert Companion and that there are ways that printed text can be offered on a screen while musicians are playing, in a way that would be acceptable to everyone. Furthermore, it can be delivered inexpensively. My idea is not to try to offer simultaneous descriptions during performances but rather to offer colorful and informative text during rehearsals.

Rehearsals offer one of the best ways to learn about music. You not only get to hear a work being played, but you can gain insights into how musicians think about a piece as they work on it. However, observing an actual rehearsal, without some help about what is going on, can be downright frustrating if not boring. Musicians talk to one another in ways that are difficult to hear and even if they are miked (which many of them find distracting), they often talk in musical shorthand that a non-musician doesn’t understand. And it is often difficult to figure out why they stop where they do and why they repeat certain sections. That is why open rehearsals—an offering that many musical organizations offer their patrons—can be so unsatisfying. Unless they serve as dress rehearsals with little stopping, they can tend to be fairly tiresome. In some cases, orchestras have offered open rehearsals as mini-performances with scheduled stops. The conductor is miked and he or she will address the audience to say what it is they are working on at a certain moment. But entertaining as these may be, they are not true work sessions and mostly are staged run-throughs.

Now imagine that you are sitting in a real rehearsal (or watching it on a screen) and a trained musician who is not playing is offering commentary in real time that you can read on a screen. For example:

The musicians just stopped and are discussing whether a repeated passage should have an echo effect the second time it is played. They are going to try it that way. Listen to the effect when they play that thematic material boldly the first time and quietly the second time.

or

The basses and cellos are in unison here and they are trying to make sure they are in tune with one another. That is why they are playing those notes so slowly. Each player is adjusting his or her pitch until they get the intonation just right.

There could also be a comment about what is about to happen—much like the Concert Companion would offer:

Near the end of the final movement, you will hear the opening theme from the first movement returning. This is unusual since in most compositions, themes stay within movements. I will let you know the moment it happens. It is quite dramatic and you should observe how the musicians are working to enhance the emotional drama.

If one wanted to add another feature, one could allow interactive chat so that audience members could ask questions. This might be featured at specific moments (for example a rehearsal break or after the rehearsal is over) so as not to distract from the running commentary, or it could be provided by a second commentator also in real time.

The Rehearsal Companion, as we might call it, could solve a number of problems that the Concert Companion faced. It does not need customized hardware or software. One could provide the text via the chat function in Zoom, for example. It does not distract from an actual performance either for the musicians playing or other audience members. It does not require pre-prepared text nor synchrony in presenting it. In a sense, it is music education at its best with real musicians playing and another musician analyzing and explaining a piece before your eyes and ears. Is it time to try it out?