The Tyranny of Specialization by Thomas Wolf

Many years ago, as I was finishing graduate school and applying for my first full-time job, I began working on what I hoped would be an impressive resumé. In describing my activities, I modeled my outline on the life of my uncle Boris Goldovsky, a true Renaissance man. I certainly couldn’t match his wide experience. A pianist who played regularly with his mother in Carnegie Hall, a respected conductor, a lecturer who had won a Peabody Award for his national radio broadcasts and appeared regularly as an intermission feature for the Metropolitan Opera, a producer and stage director, a teacher and coach, an author of books and articles on diverse subjects, a translator of libretti from any one of the eight languages in which he was fluent. He had even briefly been a chess champion.

Can a concert pianist also be a chess champion? How realistic is it to have multiple professions in an age of specialization?

Not having much of a work history on which to draw, I dug up whatever I could, leaving out the details that would minimize (in a fully frank manner) the stated accomplishments. Flute soloist with the Philadelphia Orchestra at age 16 (true it was only for a student concert), winner of a national prize for my personal library (my competitors were other undergraduates), company manager of a touring opera company for several weeks a year (I carefully neglected to mention that it was my uncle’s company and nepotism had come into play), published author (one of my psychology papers in graduate school had made it into an obscure academic journal), artistic director of a (quite modest) summer chamber music series, and someone credentialed with a Harvard doctorate (I didn’t mention that it was in a field completely remote from the one I was about to enter). Nevertheless, when I finished, I thought I looked awfully good on paper. I then showed the draft to my uncle.

“Heavens!” he exclaimed. “This is bad. You will appear a complete dilettante to the selection committee. You must redo this.”

Thinking that his criticism had mostly to do with my carefully edited descriptions, I was surprised when he asked: “What is the job you are applying for?”

It was coordinating a performing arts touring program—booking and funding performances in the six New England states.

“Then for heavens sake, that is what your resumé should be about.”

My Russian uncle continued. “These days, especially in America, people want specialists. They assume that unless you specialize, you cannot be good at something. It is not like when I grew up in Russia and Western Europe where people appreciated the breadth of a person’s experience and knowledge. It is especially problematic in the arts and in the music field these days.

Conductor Leonard Bernstein in his other roles as composer and pianist. Was it really possible to do all those things well?

“Look at Leonard Bernstein,” he continued, at a time when Bernstein was conducting the New York Philharmonic. “The man is a genius. I worked with him at Tanglewood. He is a superb conductor, he is a terrific pianist, he composes operas as well as symphonic and chamber music, his Broadway musicals are incredibly successful, he is giving the Norton lectures at Harvard on the universality of musical language drawing on his knowledge of linguistics, aesthetic philosophy, acoustics, and music history. He has produced what is probably the best music education programs for children on television. I could go on and on. Yet, he drives the critics crazy. They can’t stand it and they crucify him. With their own limited abilities, they just cannot imagine anyone so gifted in so many ways.”

I was reminded of this conversation recently as I read a piece by an oft-quoted and widely read cultural commentator, Norman Lebrecht.[1] Entitled “Don’t Shoot the Pianists, Protect Them”, it railed against the current practice of conductors who sometimes perform as pianists, especially in chamber music and recital settings. “Put a conductor at the piano and the particular intimacy of a chamber recital is jeopardized,” he asserted [as if conductors cannot distinguish the approach to leading an orchestra and playing piano—a somewhat absurd generalization]. According to Lebrecht, “Soloists are trained to defer to conductors and conductors are accustomed to being followed.” [What about conductors who follow the lead of soloists in concerto performances? I wondered.] “The parity between performers that is the essence of good chamber music is lost between bars,” he continued. For Lebrecht, it seems, specialization is essential for someone to be good.

And as if to prove my Uncle Boris’ point about critics hating the idea of musicians who can do more than one thing well, Lebrecht quoted the late Harold Schonberg of the New York Times about Leonard Bernstein: “Schonberg…missed no opportunity to disparage the quality of Bernstein’s playing and the shamelessness of his audience flirtation. ‘How much glamour and popular buildup can serious musicianship survive?’ he demanded.”

Mezzo-soprano, Magdalena Kožená appearing with her husband, Simon Rattle, in a song recital, with the conductor in the role of collaborating pianist.

There are all kinds of reasons why conductors appear as chamber music pianists (including when they play for soloists in recital). Sometimes it is to accompany a spouse as in the case of Simon Rattle accompanying his wife Magdalena Kožená in song recitals, something he does extremely well.

At other times, it may be for very practical reasons as when a soloist wants to fill a large hall and requires a big-name pianist to help out. When the baritone Hermann Prey gave a recital in Carnegie Hall on December 14, 1992, for example, he scuttled his regular pianist, the remarkable Leonard Hokanson, and used conductor James Levine, who at that time was a huge audience draw. Prey and his manager were concerned that the appearance of empty seats in Carnegie Hall would put the singer at a perceived disadvantage in comparison with his long-time rival, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, who regularly filled the auditorium.[2] Nevertheless, though the decision was not primarily a musical one, according to those at the concert, Levine played beautifully and did not seem hampered by the fact that he was also a conductor.

Lebrecht does make an important point with which I am in complete agreement. For decades, pianists who played for great soloists were perceived as lesser musicians, merely “accompanists.” I come from a family in which three pianists played for big-name musicians on multiple occasions so I am keenly aware of the issue. Conversations around our dinner table often addressed the need to insist on equal billing in publicity materials and printed programs for the pianist. After all, my relatives were making a substantial contribution to the musical success of the event. To some extent, the likelihood of receiving such billing was generational as attitudes changed. When my great uncle Pierre Luboshutz performed with violinist Efrem Zimbalist or toured with double bass virtuoso Serge Koussevitzky almost a century ago, Pierre’s name was often difficult to find in publicity materials or reviews. Yet half a century later, when my brother Andrew Wolf appeared with violinist Isaac Stern or cellist Leonard Rose, posters and programs often included his name in the same size type as those of his partners. Today, the role of assisting pianist is considered so important that conservatories have special concentrations devoted to the practice for students who want to make it their chosen profession.

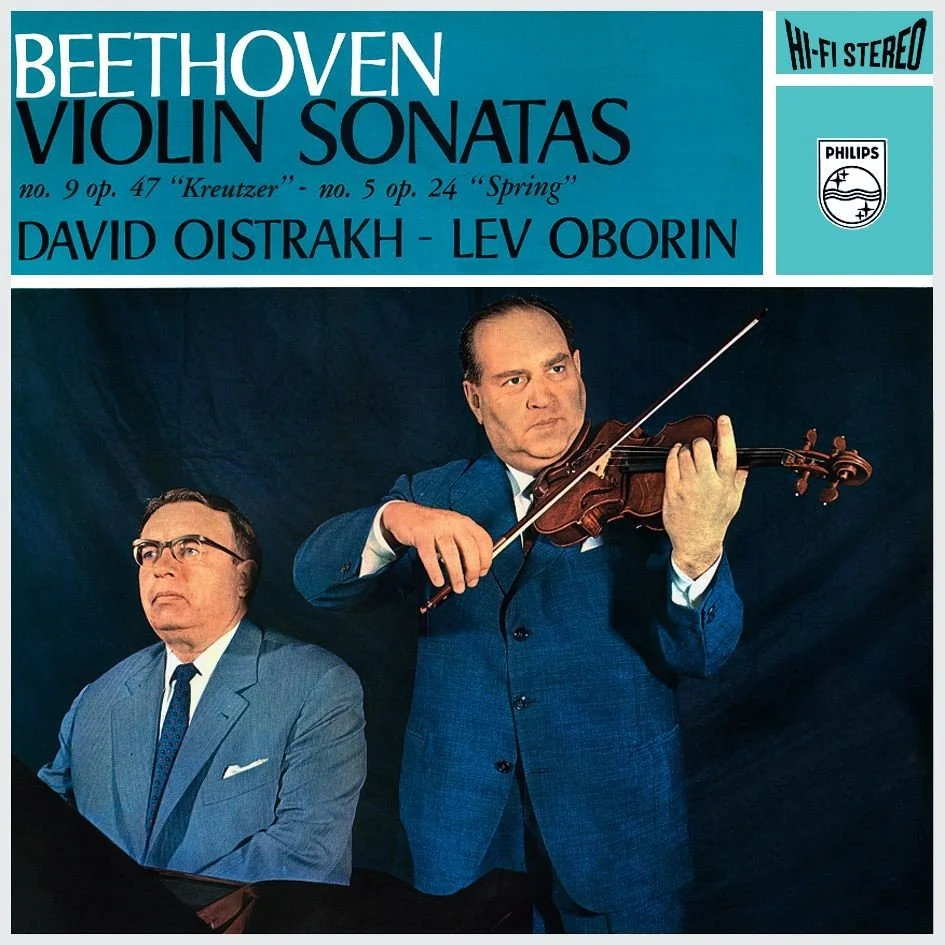

Can one imagine the iconic recordings of David Oistrakh with a pianist other than Lev Oborin?

Lebrecht celebrates the role of assisting pianists citing many whose contributions have been indispensable to the musical quality of performances—Gerald Moore with baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Lev Oborin with violinist David Oistrakh, Lambert Orkis with violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter, and Helmut Deutsch with tenor Jonas Kaufmann—Lebrecht calls them “indispensable partners.”

And when the repertoire they play requires at least as much musical prominence for the pianist as for the partner—think of a conventional violin recital consisting of sonatas by Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, and Franck—the invisibility of an “accompanist” is totally inappropriate.

Finally, Lebrecht decries the practice of conductors who not only play piano but do so while conducting an orchestra. He fails to mention that Mozart did this regularly with his piano concerti and also conducted his operas from the keyboard, accompanying singers in recitatives. Lebrecht again mentions Bernstein and uses as his Exhibit A, a performance of Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” in which Bernstein is both piano soloist and conductor. The performance is available on YouTube and I decided to watch it and form my own judgment. (I invite you to do so as well.) It is hardly my favorite performance of the piece—the playing is quite mannered for my taste and sometimes the orchestra and piano are not quite in sync. But it is great fun to watch and listen to such a tour de force. For me it is more entertaining and satisfying than some of the mechanistic and predictably technically “perfect” performances of many of the younger generation of so-called “superstars.” To each his own, I guess.

Yuja Wang coming on stage to perform Rhapsody in Blue by Gershwin.

Interestingly, once the Bernstein video finished in my viewing, YouTube switched me automatically to a performance of the same work by the pianist Yuja Wang. As the video began, the pianist appeared on stage in what I can only describe as little more than a black bikini and high heels. Being somewhat of a traditionalist when it comes to the dignity of concert attire, I found her appearance offensive and off-putting. I didn’t even bother watching the rest of the video. Once again, to each his own.

[1] Full disclosure: Lebrecht wrote some complimentary paragraphs about my book, The Nightingale’s Sonata, in the Wall Street Journal soon after it was published.

[2] A few years later, Hokanson parted ways with Prey. The perceived disrespect on the part of the singer owing in part to the Carnegie Hall decision was a factor in Hokanson’s decision.