“Ella Mi Fu Rapita” By Boris Goldovsky Presented Publicly for the First time by Thomas Wolf

In 1959, my uncle Boris Goldovsky finally wrote down a story he had been telling at family gatherings for years. At the time, it would not have been politic to publish it so he issued a very limited edition of only eight copies for family members.

Now for the first time, this wonderful story can be shared more widely.

In the year 1936, I was offered the post of conductor with the Singers Club of Cleveland, a choral society of about one hundred professional and business men who “sang for the fun of it,” and did it extremely well. I had never worked with an all-male choral group before and was somewhat reluctant to undertake the task. I discovered, however, that the Club had done relatively few operatic selections so that I was in a position to capitalize on my special knowledge in this field. There were any number of fine operatic male choruses and I was anxious to hear them sung by a well-trained group of a hundred men. The directors of the Club were also a trifle nervous, for I was young by their standards [28 years old] and was altogether an unknown quantity.

Singers Club of Cleveland

To protect their first concert to some extent at least, they engaged a popular guest star, the famous Italian tenor, Tito Schipa, who had sung with the Club before and was a great favorite of the Cleveland audiences. Since Schipa was an opera singer of great repute, I decided to have him collaborate with the Club in an operatic excerpt where he and the Club members could show off, both separately and together. I was looking for an interesting scene involving a tenor and a male chorus and I immediately thought of Verdi’s Rigoletto.

The second act of this opera opens with a very well-known solo for the Duke of Mantua, an Aria wherein the Duke laments the loss of his beloved. It is known by the opening words of its introductory Recitative, “Ella mi fu rapita,” and is followed by the chorus of courtiers who enter in great excitement for they are eager to tell the Duke of their latest escapade.

The courtiers have succeeded in abducting a young girl whom they believe to be the mistress of the court jester, Rigoletto. They hate the hunchbacked jester and sing with great glee of the vengeance they have taken upon him. The Duke soon realizes that the abducted girl is none other than his beloved Gilda, Rigoletto’s daughter. Learning that the kidnaped girl has been secreted nearby in the palace, the Duke expresses his joy in a second soliloquy which he sings in what is known as an “aside” since he has no intention of revealing the girl’s identity to the courtiers. Near the end of this second Aria, the choristers whisper among themselves, commenting upon the Duke’s sudden excitement and obvious delight, which they quite rightly interpret as being of amorous origin. As the scene closes, the voices of the courtiers and of the Duke mingle in a final section which gets faster and louder and culminates in several exclamatory high A’s for the tenor which are supported by full-throated choral accompaniment.

The legendary tenor Tito Schipa

This scene was just exactly what I was looking for. The role of the Duke was one of Tito Schipa’s best impersonations and the sequence of dramatic Recitative, melancholy Aria, male chorus scene, and rousing Finale for soloist and chorus was perfect for the Singers Club concert.

There was only one disturbing possibility in this otherwise ideal set-up—it was by no means certain that Schipa would consent to sing the second Aria, the one with the chorus accompaniment. This number, unfortunately belongs to the category of those which are usually omitted in performance. Nor is there anything particularly exceptional about it.

There are not too many Italian operas that are performed precisely the way they were composed and published. Not only do singers add high notes and transpose Arias to higher or lower keys, but quite often entire sections of a work are cut out. The origins of these changes are usually obscure, but once a version has become “traditional,” it is treated with an almost religious respect. I imagine that at some point, a particularly famous tenor playing the Duke of Mantua decided that the D major Aria was too heavy, too “dramatic” for his voice. Three tenor arias in one opera were enough for him and so the fourth one went by the board, in spite of the utter nonsense of having a leading character leave the stage without reacting to the exciting news he had just received. It did not take long for the other impersonators of the role to catch on and soon the “cut” became traditional and irrevocable. Even today in the late 1950s, when producers and conductors have become much more adventurous, this D major Rigoletto Aria is heard only rarely. In the year 1936 it was, for all practical purposes, non-existent. In all the performances of Rigoletto that I had witnessed in Europe and in the United States, this piece had been omitted. On the other hand, I knew that [one of the greatest interpreters of Italian opera, the conductor, Arturo] Toscanini was violently opposed to such blind adherence to traditional procedures and it was possible that Schipa had sung this section of the opera either with Toscanini or with some other progressive conductors.

Boris Goldovsky rehearsing the opera chorus

Having located Schipa’s address in Italy, I wrote him a very polite letter, asking whether he would agree to sing the complete Rigoletto sequence as I outlined it to him. When after six weeks, there was no answer, I wrote him a second letter and mailed a copy of it to the New York concert agency which had booked Schipa with the Singers Club. By the beginning of November, there was still no word from Schipa and I began to feel jittery. The members of the Club were certainly learning the music and the Italian words to my complete satisfaction, but the possibility that the key group of my first concert would fizzle out at the crucial point was causing me sleepless nights.

Then I received a letter from Schipa’s booking agents in New York. They were sorry, they wrote, that they could not answer my query concerning their artist’s attitude to the D major Aria in Rigoletto, but Signor Schipa was still touring his native Italy and was seemingly beyond the reach of written words. They had a suggestion, however, namely that I discuss my problem with Signor Egidio Prandicelli, Schipa’s representative, advance agent, and personal friend, who was on his way to Canada to organize the tenor’s touring schedule for the following year. This gentleman was thoroughly acquainted with Schipa’s repertoire and since he was planning to visit Cleveland the following Monday, he would be glad to assist me in settling all questions concerning the program. Things began to look up. I called Prandicelli on Monday and he sounded very cordial and readily accepted my invitation to meet and dine at Luccioni’s at six thirty that very evening. Luigi Luccioni ran an excellent Italian restaurant and was a rabid opera lover. When I told him of Prandicelli and of our scheduled discussion of Tito Schipa’s program for the Singers Club, he was only too eager to reserve the best table, and promised special attention, the choicest of wines and the rest of it.

I felt that my best hope lay in ingratiating myself with Prandicelli and asking for his help. If Schipa knew the Aria and was willing to sing it, then of course, all was well. If he knew it and was reluctant to perform it, then possibly Prandicelli could persuade him to be more co-operative. Finally, if Schipa did not know the Aria at all, Prandicelli might induce him to learn it in time for our concert. Musically speaking, the piece was simple enough and Schipa should be able to memorize it in a matter of days. If the worst came to the worst, I would not object having Schipa use the score in performing it, although it would look a trifle silly to have him sing “Ella mi fu rapita” from memory, and then hold the book for the ending of the same group.

All these contingencies and possibilities were racing through my head as I was waiting for Schipa’s friend at Luccioni’s. Prandicelli arrived right on time. He was a jovial-looking, pot-bellied man, quite elegantly dressed and full of vitality. He spoke English at a surprising rate of speed, with a fluency which was not at all impeded by his heavy Italian accent. As a matter of fact, his habit of attaching additional vowel sounds to English words seemed to give his enunciation an even greater power of propulsion. It had been years since he had visited Cleveland, he said, but he remembered Luccioni’s and was looking forward to our conversation. After ordering the meal, we spent several minutes in exchanging the usual generalities on the weather, on traveling conditions, and on the differences between American and Italian cooking. Prandicelli started telling me of the heavy storms which had plagued his recent crossing of the Atlantic, but the arrival of the hors-d’oeuvres helped to slow down the tempo of the conversation and opened the way for the broaching of the main topic of our meeting. I felt that the sooner I could acquaint him with the situation the better, and so I plunged right into the meat of the subject.

“I do hope, Signor Prandicelli,” I said, “that you can help me set the program for the Singers Club concert here, in December. I have written two letters to Mr. Schipa but I have received no reply to either one of them.”

To Prandicelli, this must have been an old and familiar story. “Oh, you know how it is,” he said, “Tito Schipa is-a great tenore, a famous-a star, e un gran artista, but is not a great-a scrittore. He do not-a write letters, not even to me…he sing-a, but he do not-a write-a!” Prandicelli laughed heartily at his own joke.

“Naturally, I understand,” I assured him. “Now then, the Singers Club and I, we are of course, delighted to have Signor Schipa as our soloist here in December. Tito Schipa is a marvelous artist and…”

“Ah, si…meravigloios...veramente meraviglioso…” Prandicelli shook his head in devoted rapture, without, however, neglecting the antipasto.

“You see, Mr. Prandicelli, this is my first season conducting the Club, and so it is most fortunate that we were able to secure the services of an artist who is so popular with audiences here.”

“Ah yes, that was-a very clever-a, very clever-a…” Having done justice to the olives, Prandicelli turned to me. “I must-a congratulate-a you, young-a Maestro. With Tito Schipa, you always have gran successo, not only with audience, but also with press and with—what-a you call—box office-a.” He pronounced the last as boxafeece-a. “I trust, he added, “that you have received all the necessary publicity material and pictures?”

“No problem there at all, Signor Prandicelli, none at all. My letters to Mr. Schipa were concerned with the program, particularly with the main group which is to come just before the intermission. Here, I would like Mr. Schipa to do a sequence form Rigoletto.”

“Ah, Rigoletto!” Prandicelli gazed upward to emphasize the heavenly quality of Verdi’s opera. “It is wonderful idea to have Schipa sing-a Rigoletto. E una vera ispirazione…how you say…ispriation! Schipa, he sing the Duca of Mantova everywhere-a with the most greatest successo. In the last-a two year, he sing it in-a Roma, at-a la Scala in-a Milano, at-a the San Carlo in-a La Fenice, not-a to mention-a Bologna, Parma, Pisa, Firenze and Genova.” (I was about to say something, but he stopped me.) “No, essacuse me please! Genova, that was-a three year ago, but Milano, Roma, Napoli, Venezia, Bologna, Firenze and Pisa, that was all-a in the last two year.”

The waiter was removing the antipasto plates. “Yes, I know, of course…” I tried to interject, but Prandicelli became even more voluble,

“And-a Torino, Dio mio, Torino!...goodness gracious, how could-a I have forgotten Torino. Che successo, che trionfo! I do not-a esagerate-a…believe me, Maestro, I am not-a one to esagerate-a,...but in Torino, when the opera, she finish, the public it do not-a leave! It-a refuse to leave the teatro! Schipa, he come out-a to bow twenty-five or thirty time-a, but still they REFUSE-A TO GO.” He gazed into the distance, reliving it in his mind’s eye and savoring anew the amazing spectacle of the Turin opera house filled to capacity with Schipa admirers who stubbornly refused to go home.

Fortunately, the waiter brought a terrine of steaming chicken soup, the aroma of which brought Prandicelli back to earth and gave me a chance to continue with the presentation of my problem. “You see, Signor Prandicelli, I would like to begin this group on the program with Mr. Schipa singing the ‘Ella mi fu rapita’…”

“‘Ella mi fu rapita?’” he exclaimed, “ma bravo! Oh bravo, bravo!” He pushed his chair away from the table and gazed at me with what appeared to be genuine admiration. “‘Ella mi fu rapita!’” He rolled the r’s and savored the Italian syllables as if they were some rare and delicious morsel. “Tito Schipa, he will-a sing-a ‘Ella mi fu rapita!’ Che meraviglia, che successo! You have-a taste, Maestro, I must-a tell you that this Aria, ‘Ella mi fu rapita,’ Schipa he cannot ever-a sing-once-a! You surprised? Ha, ha, do not-a be surprised, Tito he alaways sing it-a twice-a! At-a La Scala must-a repeat and sing it-a twice-a, and at San Carlo, at the Fenice, alaways twice-a. Also Bologna, Pisa, Firenze…as soon as he finish ‘Ella mi fu rapita,’ the public it go crazy. Is impossible to sing-a once-a! But, listen-a to this! At-a Torino, when they refuse to leave the teatro, two year ago, Schipa he had-a to sing-a this Aria three time-a. Believe me Maestro, I do not esagerate. But this is-a nothing! Ten year ago, in Parma, I was there myself, and saw it-a with these two eye…”

Prandicelli pulled up his chair and moved closer to me so that he could grasp my arm with both his hands. “You do not-a know the Parmigiani? No? Well-a they are terrible public…terribili! When they do not like il tenore, they are ready to kill! The police, it must-a take the tenore quick from-a the teatro and put him on the train, to save-a his life-a!...When they like the singer he must do what they say. Listen…”

Here Prandicelli shook the extended thumb of his right hand, “Schipa he sing ‘Ella mi fu rapita’ and then…” here the index finger joined the thumb, “he sing it again. But that is nothing…he know he alaways sing Aria twice-a. Then, the choristi they start coming out on stage, but the Parmigiania scream-a so, the choristi they go back fast-a and...” now the middle finger joined the others, “and he sing-a third-a time. But wait-a, wait-a! come-a the best. After he sing-a third-a time, the public, they jump up……stamp-a- feet, yell ‘bravo, bis, bis’,…Schipa, he afraid he get-a tired out…must-a still sing-a the whole-a last act! Misericordia! Schipa, he point to his throat, beg public, ‘please, non posso più…I sing already three time-a…three time-a enough!’ Ma no! the Parmigiani, they are assassini, make-a him sing it four time-a!”

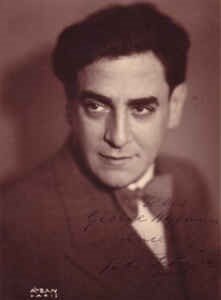

Boris Goldovsky at about the time the dinner with Signor Egidio Prandicelli took place

Prandicelli leaned forward and shook both arms with four fingers extended on each hand… “‘Ella mi fu rapita’ once-a, and again-a, and again-a and four time-a!” He sank back in his chair just in time for Luccioni’s famous Polpettone alla Napolitana.

“How wonderful, I said, “but here, as you know, the audiences are less demonstrative.” Prandicelli agreed silently, he was too busy to speak. It was now or never, I felt. “When Schipa finishes the ‘Ella mi fun rapita,’” I added hurriedly, “the Club members will sing the chorus, ‘Duca, Duca.’ They sing it in Italian, by the way, and do it very well, I assure you. After the chorus gets through with this number, we come to the final section of this scene, and it is here that I probably will need your help, dear Signor Prandicelli. At this point, there is an Aria for the Duke, a very fine, exciting Aria in D major—'Possente amor ni chiama’—where the chorus joins at the end, and you see, I am not sure the Signore Schipa knows this Aria. I am not certain, you understand, and I wrote him about it, but as you know there was no answer. Now, I wonder… if he does not know this Aria, maybe you could ask him to learn it for our concert?”

Prandicelli looked at me in wide-eyed amazement. “What-a you say?” he finally uttered, “I should-a ask-a Schipa to learn Aria from Rigoletto? Because, he, Schipa, he do not-a know Aria from Rigoletto?” He wiped his head with a large handkerchief and I was just about to open my mouth for an explanation, when he stopped me by pointing an accusing finger in my direction. “You say, Schipa, he do not know Aria from Rigoletto? Gran Dio! Me, Egidio Prandicelli, I have-a to travel in this-a barbarian country, all-a the way to Clayvelando Oheeo, to hear young man-a (essacuse-a me, I do not remember-a your-a name-a), hear a young American Maestro, tell-a me, Prandicelli, that Schipa HE DON’T KNOW ARIA FROM RIGOLETTO! Tito Schipa who sing-a Rigoletto in every teatro, in every opera’ous-a in the world-a, at-a La Scala every year-a, at-a San Carlo, at-a La Fenice, in-a Rome, Ferrara, Pisa, Bologna, and Genova…Never sing-a once-a, alaways twice-a…No, at-a Torino, at-a Parma three and four-a time-a—But here in Clayvelando Oheeo, he Schipa, he do not-a know…DO NOT KNOW ARIA, he must-a learn-a Rigoletto! Dio Mio, che ignoranti! Essacuse-a me—young-a man for I cannot remember your-a name-a, but it is-a for me, Egidio Prandicelli, it-a is-a not-a possible to go to Tito Schipa and-a say-a to him-a: Please-a, Signor Schipa, in Clayvelando, Oheeo they ask-a you learn Aria from Verdi’s Rigoletto. There is young Maestro Americano who, he is not-a certain, but he do not-a think you know Aria from Rigoletto, so he ask-a me, Prandicelli, to ask-a you, Tito Schipa to please learn Aria from-a Rigoletto, so you can-a sing Aria in Clayvelando!”

The rest of the dinner was a dismal and chilly postlude of mercifully short duration. Now that the Prandicelli meeting proved to be a fiasco, there wasn’t much else I could do except hope for the best. Just to clear my conscience, I wrote another letter to Schipa telling him that I did not care whether he sang the Aria from memory or not. As the date of the concert approached, I kept telling myself that I was worrying about nothing and for no real reason. Even if Schipa did consider the Aria too strenuous for the opera proper, he certainly could not object to singing it in a concert such as ours where he had a relatively simple and easy talk. The night before the concert, we held a dress rehearsal. Schipa had arrived that afternoon and was taken out to dinner by a few of the older directors of the Club. I told them not to hurry with the meal, since I could rehearse without Schipa for a good hour and a half. The truth of the matter was that I wanted the members of the Club to be nicely warmed up by the time Schipa arrived so as to make a good impression upon our famous guest. Eventually Schipa appeared and seemed to be in the best of spirits. He sang the “Ella mi fu rapita” like an angel, listened respectfully to the choristers in their “Duca, Duca,” and made complimentary noises apropos of their Italian enunciation.

After the choristers finished their section, I gave the upbeat for the introduction to the D major Aria, but when the time came for the tenor to sing, Schipa just kept standing there and looking at me with a puzzled smile. “Un momento, Maestro,” he said in his high-pitched, melodious voice, “what is-a this music that-a they are playing?”

This was too much for me and I nearly exploded from sheer frustration. “But dear Mr. Schipa,” I said, barely managing to control myself, “this is the Aria about which I kept writing you. I sent you three letters. Surely, you must have received at least one of them. If you are not going to sing this Aria, then how on earth will we end this Rigoletto group? It cannot just be left hanging there in the air on that final choral chord. Didn’t you get any of my letters?”

“Please, Maestro, may I see this place in the score?” asked Schipa, who remained completely unruffled during my anger outburst.

“The score? Why, here it is in the score… “Possente amor mi chiama”…where it has always been, ever since Verdi composed it, eighty years ago!”

I was too upset to keep up a pretense of good manners.

Schipa looked at the score and then shook his head sadly. “Oh, that is-a too bad,” he said, “that is-a too bad!” He returned the score with a look of sincere compassion. “You, young American Maestro should ask-a somebody who know Italian opera, you should-a consult and ask-a. You could save much-a trouble if only you ask-a. Anybody who know Italian-a opera could-a tell you that this Aria SHE NEVER-A DONE-A! But it is not such a great tragedia. When the chorus they finish to sing, I sing ‘La donna e mobile.’ The people out-a there,” he indicated the empty rows of the auditorium, “they like-a very much ‘La donna e mobile.’ You will see, Maestro, it will be much-a great successo!”

Dramatically, of course, this was absurd and made absolutely no sense. Instead of the Duke expressing his joy that Gilda was nearby, he would be singing about the fickleness of women. And yet, under the circumstances, it was the only possible solution. I was horrified at the outlandish notion of having the Duke of Mantua singing the Italian equivalent of “…she is always lying. Always miserable is he who trusts her…” after learning that Gilda (who has demonstrated that she is just about the most faithful of all Italian operatic heroines) is in the palace.

But the funny thing was that, in a way, Schipa proved his point. No one noticed the frightful mismatching of the continuity of the plot and the entire group had an enormous successo, just as he had predicted

I think I would have forgiven him that, but there was a final indignity which rankles me to this day. For the Cleveland audiences applauded so loudly at the end of the Rigoletto group that Schipa actually had to repeat the “Donna e mobile,” and it is the look that he gave me as he sang it again that left a mark that time has not yet succeeded in erasing.

A little smirk aimed at Boris Goldovsky followed Schipa’s great success in Cleveland