New Offerings in Leporello's Catalogue by Thomas Wolf

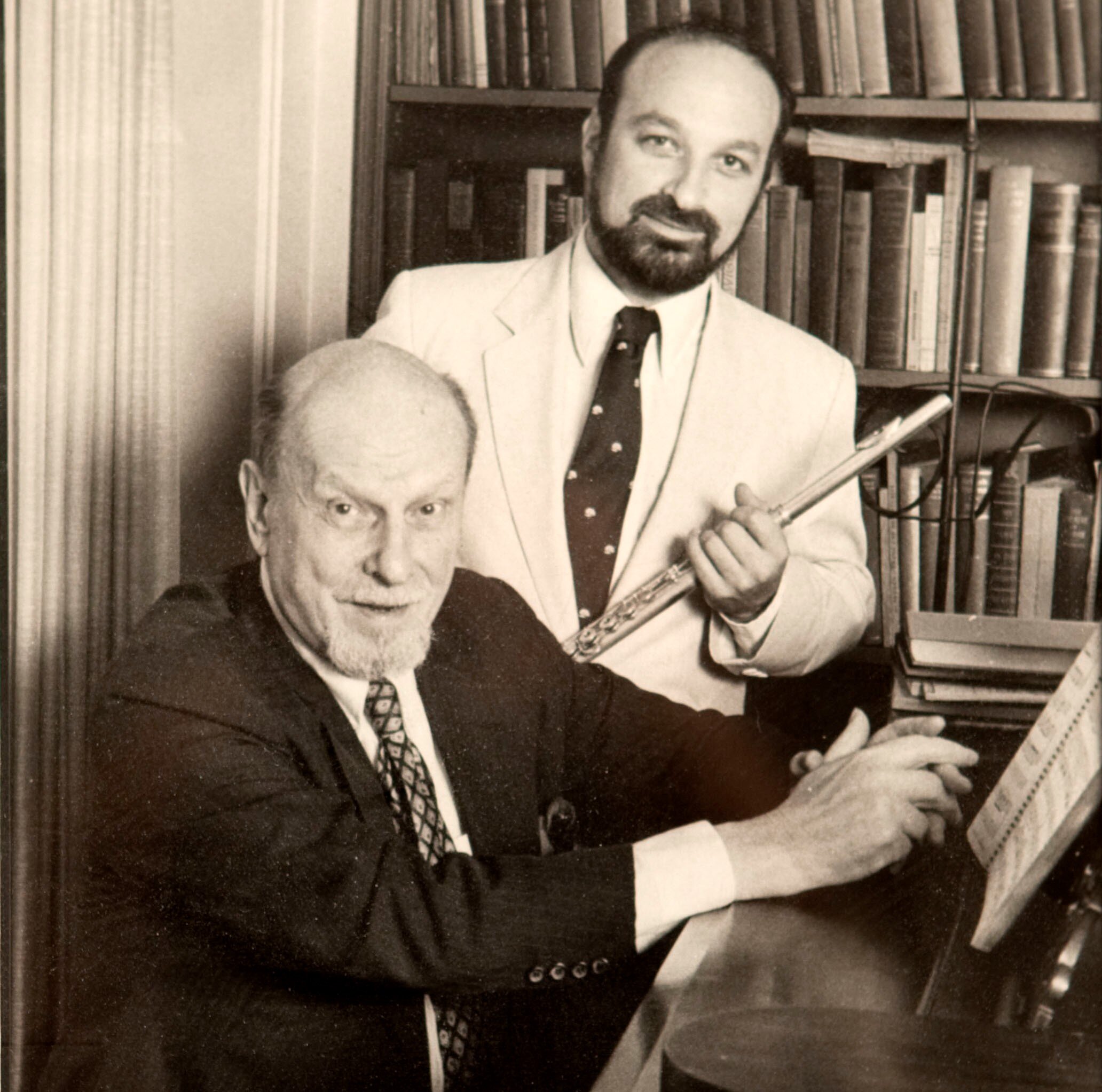

My Uncle Boris Goldovsky’s favorite opera was Mozart’s Don Giovanni and there was nothing more fun for me than playing first flute in his touring opera orchestra night after night, especially when he was on the podium conducting. I was 25 years old the first time I had occasion to so do.

It was 1970. My wife Dennie and I had been accepted for graduate study at the Harvard University Graduate School of Education. Boris had invited me to become the company manager and flutist of Goldovsky Opera Theatre. I was excited for many reasons, not the least of which was that income from the tours would more than cover my tuition expenses. At first, I had demurred, thinking that taking five or six weeks away from school in both the spring and fall semesters would cut into my studies. But my professors were intrigued and accommodating and designed a course of independent study that allowed me to do both the school work and the performing. During the spring of 1971, I went on my first tour—five weeks of Mozart’s Don Giovanni—but not before Boris gave me a workout on the flute part so that I would be sure to play it flawlessly. The last thing we wanted was to be accused of nepotism where I was concerned.

Once on tour, every night I would get to play Mozart’s magnificent music and would look forward to one of the most famous moments in all of opera – the “Catalogue” Aria. Not only is the music delightful, but the stage antics are quite amusing. For those who do not know the opera, the situation is this: Leporello, the faithful servant of the nobleman Don Giovanni, is recounting the Don’s exploits with women to one of the Don’s jilted lovers, Donna Elvira. Leporello has recorded all of the deeds (or misdeeds) in a catalogue. Donna Elvira becomes increasingly anxious during the scene to see what Leporello has written about her in the catalogue. In Boris’s staging, after listening to Leporello’s summary of the Don’s actions (including 1,003 women in Spain alone), Donna Elvira finally snatches the catalogue from him and, assuming she was the last of the Don’s conquests, turns to the final page. Leporello shakes his head sadly and turns back many pages, indicating that there have been other women in the Don’s life since her time with him.

It is not easy to be Donna Elvira during this scene, since Leporello has all the singing and most of the stage action. About all the soprano can do is express her surprise and upset at each new revelation. She has to save her biggest response until the very end and manage to prolong it through what is inevitably the long applause that follows the end of the aria. Much as everyone in the audience is focused on Leporello, Elvira has to enhance the humor of the situation. I always marveled at skilled sopranos who could pull off this tricky bit of companion stage acting. One of Boris’s specialties was teaching singers how to act.

We always toured with two singers for each of the major roles since no singer can perform every night for several weeks on end. One of our Elviras for the 1971 tour was a seasoned professional who had done the role many times. The other was doing it for the first time. Rather than deferring to her senior co-character, the younger woman behaved like a true prima donna, often explaining how she really understood the role better than most women and though she might be young, others could benefit from watching her. This lack of modesty was a thorn in the side of many of us in the company.

After a few weeks of her haughtiness, several company members decided something had to be done about this untenable situation. By this time, she was comfortable in the role and, as happens so often after many performances, she was coasting on auto-pilot. Nothing untoward had occurred so far and we felt that she was overconfident. An accident-free performance night after night is not the way of the opera world. Inevitably something unexpected will occur and this is what separates the great from the merely good. An experienced professional knows how to respond when things go awry but we were not convinced that our novice would be ready. And it might be a good idea to knock her down a few pegs. A group of “troublemakers” in the company decided they would not wait for fate to intervene but would provide some kind of an on-stage surprise. How would our soprano react if there was a little something unexpected in the final moments of the scene?

Now I should say that at this point, I was a bit uncomfortable with what was in the works. I knew Uncle Boris would not approve of such a thing. Jokes were fine, but not when perpetrated on stage during a performance. As his company manager, I was responsible for the smooth running of the operation. But I confess that my curiosity got the better of my loyalty and, because Elvira does not sing during Leporello’s aria, I decided I could be just as curious as everyone else about what would happen and how the young soprano would react. And it was not as if we were performing in New York or Paris. By this time, we were half way across the United States playing some fairly small towns. Every performance matters, of course, but we were granted a little leeway given our location. And after several weeks on the road performing most nights, the company needed a little “pick-me-up” to reinvigorate the excitement of the first week.

Excitement was certainly generated as news traveled throughout the company though no one, including the perpetrators, yet knew exactly what the surprise would be. Then one day, we were walking through a small town and we came across an “adult” bookstore.

“I think I have an idea,” our Leporello of the evening said. Marching in, he went to the magazine rack and after careful study, picked a magazine featuring male body builders in various states of undress. “This will be perfect,” he said.

How he convinced the prop master to lend him the on-stage catalogue for the afternoon, I will never know. Perhaps Franco Boscarino, an Italian gentleman who had toured with Boris for years as chief of props, was in on the plan but I doubt it given his loyalty to the boss. Perhaps our Leporello claimed he had to study the catalogue more carefully. But borrow the catalogue he did, and, with the help of scissors and scotch tape, by the time he was through, the Elvira double page of the catalogue was filled with photos from the body-builder magazine, above which was the question, “Which one would you choose?”

I could hardly wait for the night’s performance. Neither could other members of the orchestra, who hoped that the orchestra pit was shallow enough that each member would be able to view the stage. All of us urged Leporello to move as close to the stage lip as possible during the scene and I was especially lucky because, as first flute, my chair was close to the audience and I had an unobstructed view.

When the moment came, orchestra members’ heads turned toward the stage. Boris, conducting, was puzzled but nothing seemed untoward. Then came the moment. Leporello turned back the pages and our young Donna Elvira, after a moment of shock, burst into what obviously began as laughter but was skillfully turned into a loud cry of grief, as she beautifully pivoted into character with a face that only revealed shock, and a heaving body that we knew was convulsing with laughter but the audience figured was expressing situation-appropriate sobbing. I have to admit, it was one of the most beautiful jobs of acting in the moment that I had ever seen.

After the show, we all went out for a beer and despite her previous unpopularity, the young soprano was the heroine of the moment. She had demonstrated an important life lesson: When it comes to the unexpected, make the most of it and weave straw into gold. We toasted the young woman and celebrated her performance until my Uncle came up to the table. “You know, dear,” he said, “your reactions in the catalogue aria were excellent, but be careful. You may want to tone it down a bit. You don’t want to upstage Leporello and, if you are not careful, your cries can sometimes sound a bit like laughter.”